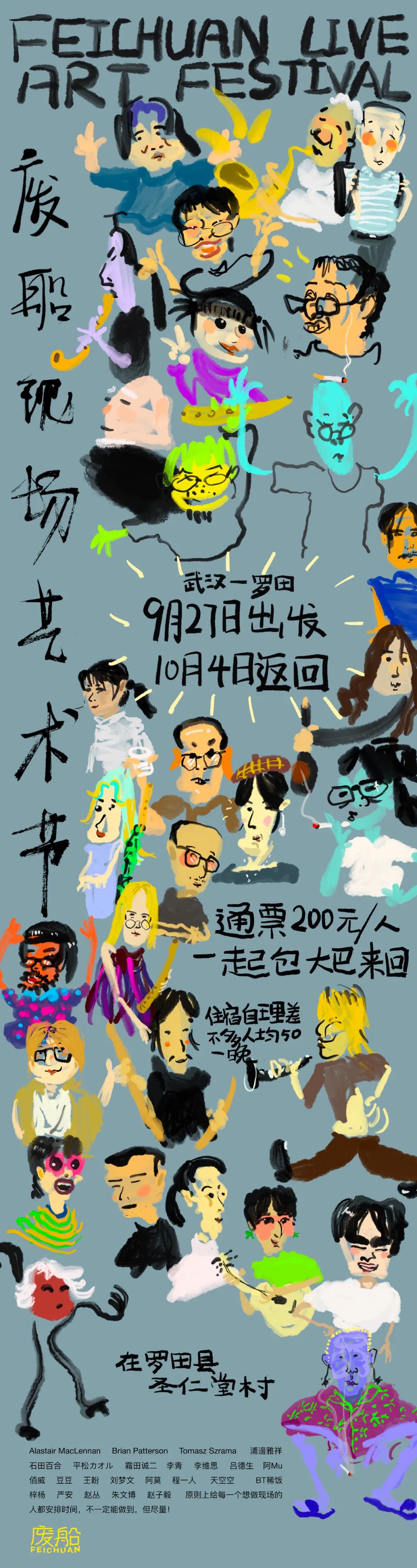

Urabe Masayoshi 浦边雅祥 at Feichuan Live Art Festival

The portion of Feichuan Live Art Festival that your correspondent attended took place in the village of Shengrentang, Luotian County, Hubei Province, China.

The day after his performance (he hates the word perform, preferring the word play — sorry, Urabe-San), at the subdued communal lunch — I know not what oppression it was the air that invariably blanketed the eaters in murmur and silence, for at all other parts of the day and especially during the night, it was a lively, noisy troupe — I happened to be sitting at a table with Urabe Masayoshi (really it was because the boss of the hotel told me to sit there. In the first few days of the festival, when the attendees were at their most numerous and the dining area was at capacity, he always insisted, emphatically, that I sit at that particular table). Yes, I was deeply impressed by his music the day before, so after a time, the discomfort at the enduring semi-silence overcame my habitual shyness and I asked him, “Why do you perform?” He thought about it for a while, and then as the very first thing, he specified that he prefers to designate whatever it is that he does as play, rather than performance. However, when he said “play”, I thought he had said “pray”, which, though plainly a misunderstanding on my part, stemming from his Japanese-inflected English as it were, was, I think, a most fitting description for his art. Turning now to my question, his answer was, “Because I really want to.” I confess that I was more than a bit disappointed. Of course, if I could converse in Japanese, I suppose he would have said something less glib. And yet, as I continued to reminisce about it all over the following days, I came to appreciate the truth of what he meant by that simple, underwhelming phrase. For, you see, it is the breath of Urabe Masayoshi’s prayer which is, I kid you not, the very thing animating his otherwise deathly skeletal frame.

Inside the emptied dining room of The Red Leaf Hotel on the afternoon of Friday the 29th of September.

I apologise profusely, Dear Reader, because this review begins, embarrassingly, with yet another autobiographical intrusion. I entered the room after the entirety of the audience was already seated, gathered in the half of the room which had on its Northeast-facing wall the entrance to the street and, opposite, the doorway into the rest of the hotel. In the other half of the room was only Urabe’s small body occupying balance of the space — seeing an empty chair beckoning in the corner behind him, and perhaps seconds before he was about to begin, I quickly crossed over and sat on it. There was a large circular strip of two or three loops of metal, or a black synthetic material of some kind, on the floor not too far from me. Here Urabe Masayoshi approached me and said, without any gestural indication, but seemingly in reference to those loops on the floor, “Dangerous.” Feeling exceedingly foolish, I departed what was quite clearly a stage of some sort, and seated myself by the large aquarium-like windows on the street-side of the room, among the rest of the audience where I belonged.

I am quite certain he had been on the verge of commencing just moments before, but now he spotted one or two thin puddles of water on the ground, left over from an event earlier in the afternoon, and, because of the risk of slipping, asked that they be mopped up before beginning, which was done. Ironically, it wouldn’t be long before the polished marble floor was re-puddled by drops of sweat that fell from his labouring body.

It began. He was moving a lot, but not in a large or Olympian fashion. He was a trembling silhouette of tortured movements: he was dancing, wielding the saxophone as a martial prop as often as he was expelling air through it. The sorry vernacular for musical instrument in the jazz milieu of my youth was axe, but the truth was that Urabe’s saxophone somehow resembled a rifle. Actually, one image that comes to mind is that moment when he was looking down the neck of the saxophone as though he were looking through the sights of a gun. There was an ever-present intensity to his gaze; it occurred to me that he looked like he was prepared to kill, kill the audience, murder in his eyes.

One leg is planted firmly on the polished stone, the other leg is bent crooked, heel raised in the air, a shaking old pressure on the ball of the foot. Airs circulate in the room. Someone started sobbing, to which our saxophonist responded. Another woman was sent into a meditation by his singing. He scraped his saxophone along the ground. At another point someone punctuated the atmosphere with an unfunny (or perhaps funny) goose-sounding horn.

Now he smashes the sole of his bare foot against the tiles with maximum force, each impact risking the knee shattering into a thousand pieces. A few local kids wandering by tapped on the window, and as with all aquariums, there was no reaction from the creatures inside. We were quite under his spell, I would venture. And then he let out a broken, exhausted and desperate grunt, and led everybody outside into the public square that was right there, where he continued. The mourner from before, now writhing around on the paving, cried out again, and some onlookers from their window on the fourth floor of the hotel were screaming wildly. And then it was over.

That afternoon, I saw a madman on the brink of death, the voice of tomorrow’s ghost singing through his still living body.